Trumpy

Donald Trump and Twitter. Say no more.

Case reviewed: Jacobus v Trump, Supreme Court, New York County

2017 NY Slip Op 27706, 9 January 2017

Background

In May 2015, Cheryl Jacobus, a political commentator and PR consultant, was contacted by the Trump campaign for a potential job as the campaign’s communications director. Jacobus met twice with Trump’s then campaign manager, Corey Lewandowski, and another campaign worker.

The first meeting went well. Jacobus’ salary requirements were sought. At the second meeting, however, Lewandowski erupted over Jacobus’ differing views as to the role of FOX television network in the Trump campaign. Afterwards, Jacobus advised she could not work with Lewandowski. No further discussions were held.

On 16 June 2015, Donald Trump formally announced his candidacy for President. In the following months, Jacobus appeared frequently on television as a commentator. She posted comments online, including on Twitter, in which she both defended and criticised Trump.

On 26 January 2016, Jacobus appeared on CNN to discuss Trump’s threat to boycott a primary debate unless FOX dropped Megyn Kelly as a moderator. Jacobus called Trump a “bad debater”. She said he “comes off like a third grader faking his way through an oral report on current affairs”. She also said he was using the dispute with FOX as an excuse to avoid the debate.

The next day, Lewandowski was interviewed on MSNBC (see from 6:35). With reference to Jacobus’ comments, he said: “This is the same person … who came to the office on multiple occasions trying to get a job from the Trump campaign, and when she wasn’t hired clearly she went off and was upset by that.”

On 2 February 2016, Jacobus appeared again on CNN, this time to discuss Trump’s claims that his campaign was self-funded. She said: “There had been a Trump Super PAC [Political Action Committee], the campaign lied about it, and then shut it down.” She also said the campaign had approached several Republican billionaire donors, all of whom had declined to donate.

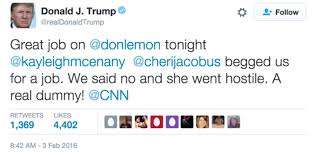

Later that night, Trump posted the following tweet:

The following day, Jacobus’s lawyer sent Trump a cease-and-desist letter.

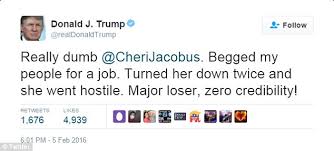

Two days later, Trump posted the following tweet:

Some of Trump’s Twitter followers responded to these tweets by criticising Jacobus’ professional conduct, experience and qualifications. As can be seen in the appendices to the claim form, some of the more extreme responses included sexually charged comments, a depiction of Jacobus with a disfigured face, and a depiction of her in a gas chamber with Trump standing nearby ready to push a button marked ‘Gas’.

In April 2016, Jacobus issued proceedings for defamation against Trump, Lewandowski and the campaign. Jacobus sought $4m and punitive damages. Her central complaint was that the defendants had falsely represented that she had sought a job from them, was rejected, and as a result made biased comments about Trump. She claimed the statements “falsely declared that she sacrificed her professional integrity to attack defendants when she was denied employment”, and made her “look terrible”. She alleged that, as a result of the statements, her professional standing “suffered enormous damage, as she became damaged goods no longer invited by the networks to ply her trade”.

The defendants filed a motion (i.e. interlocutory application in New Zealand terms) to dismiss the complaint for failure to state a cause of action. Essentially, the defendants argued the conduct about which Jacobus complained did not amount to actionable defamation.

Argument

The defendants argued that the statements in question, including Trump’s statement that Jacobus “begged” for a job and was rejected, constituted hyperbolic rhetoric, too vague to be defamatory.

Jacobus, meanwhile, argued that whether she sought the job and was rejected, was a straightforward issue of fact.

Judgment

New York State Supreme Court Judge Barbara Jaffe accepted the defendant’s arguments:

Trump’s characterization of plaintiff as having “begged” for a job is reasonably viewed as a loose, figurative, and hyperbolic reference to plaintiff’s state of mind and is therefore, not susceptible of objective verification … To the extent that the word “begged” can be proven to be a false representation of plaintiff’s interest in the positon, the defensive tone of the tweet, having followed plaintiff’s negative commentary about Trump, signals to readers that plaintiff and Trump were engaged in a petty quarrel. Lewandowski’s comments, overall, are speculative and vague, and defendants’ implication that plaintiff was retaliating against them for turning her down, notwithstanding the unmistakable reference to her professional integrity, is clearly a matter of speculation and opinion.

The Judge also commented that the immediate context of the defendants’ statements was “the familiar back and forth between a political commentator and the subject of her criticism”; and the wider context was “Trump’s regular use of Twitter to circulate his positions and skewer his opponents and others who criticize him, including journalists and media organizations whose coverage he finds objectionable”.

Ultimately, the Judge concluded:

[C]onsistent with the foregoing precedent and with the spirit of the First Amendment, and considering the statements as a whole (imprecise and hyperbolic political dispute cum schoolyard squabble), I find that it is fairly concluded that a reasonable reader would recognize defendants’ statements as opinion, even if some of the statements, viewed in isolation, could be found to convey facts.

Accordingly, the Judge granted the defendants’ motion to dismiss the complaint in its entirety.

Comment

It is tricky to analyse this judgment through a New Zealand lens, since New Zealand and the US assess the issue of ‘allegation of fact’ vs ‘expression of opinion’ from such different angles.

Nevertheless, whatever law is applied, it is hard to agree with the Judge’s fundamental conclusion, that whether Jacobus “begged” for a job, and was rejected, is an opinion not susceptible of objective verification.

Defendants in the US have the advantage that, if a disparaging statement is deemed to be ‘pure opinion’, then under the Constitution it cannot be actionable.

By contrast, New Zealand law separates (a) whether a statement is capable of being defamatory, and (b) whether a statement would be understood as an allegation of fact or expression of opinion. A claim may be struck out summarily if it is deemed the allegation complained of is too minor to be capable of substantially affecting the plaintiff’s reputation in the eyes of others. So statements that are merely exhibitions of bad manners or discourtesy are not placed on the same level as attacks on character. These statements generally will not be actionable. For this reason, it is unlikely that, in of themselves, Trump’s calling Jacobus a “dummy” or “major loser” would be actionable in New Zealand, although they may form part of the context in which the actionable statements could be assessed.

Moreover, were the case tried in New Zealand, it would not be enough for Trump and his co-defendants to convince the Court that the statements were understood by readers as expressions of opinion. Trump and his co-defendants would have two other elements to establish, if they were to prevail with the defence of honest opinion. They would have to prove the opinions were genuinely held. But most importantly (and implicating establishment of the former), a defence of honest opinion can prevail only if the defendant establishes the factual basis underpinning it. That is, an opinion that does not implicitly or explicitly reference its factual basis will be regarded as a ‘bare opinion’. Honest opinion does not apply to such statements, which are treated as akin to allegations of fact.

In any event, having regard to the legal principles outlined by Judge Jaffe (which appears in the judgment as a thorough synthesis of the leading New York authorities), it is still difficult to see how even under US law Jacobus’s claim could be dismissed. Similar to the New Zealand law described above, Judge Jaffe acknowledged that statements of opinion are protected only if they are either accompanied by the facts on which they are based, or do not imply that they are based on undisclosed facts. Further, if the underlying facts are disclosed but are false, such that the disparity between the stated facts and the truth would cause a reader to question the opinion’s validity, then this may be actionable as defamatory opinion.

Clearly there is gulf between Trump’s statement, that Jacobus “begged” for a job, and the facts accepted for the purpose of the hearing: that the Trump campaign approached Jacobus, and that after the second meeting she informed them she could not work with Lewandowski. Surely this is a classic case where, even if the statement was regarded by readers as opinion (and this seems unlikely) “the disparity between the stated facts and the truth would cause a reader to question the opinion’s validity”. Surely the matter warrants a trial. Time will tell – the decision has been appealed.

In the meantime, the judgement is available here.