The Jewish Cartoonist and the Anti-Semitic Teacher

Our favourite case featuring cartoons.

Case reviewed: Ross v Beutel, Court of Queen’s Bench and Court of Appeal, New Brunswick, Canada

1998 CanLII 9142 (NB QB); 2001 NBCA 62 (CanLII), (2001) 201 DLR (4th) 75

Background

On 6 May 1993, the Social Studies Council of the New Brunswick Teachers’ Association (NBTA) held a workshop for teachers related to Jewish history, traditions and culture. The focus of the workshop was on the Holocaust and anti-Semitism. The NBTA invited several speakers to make presentations.

Josh Beutel, a freelance cartoonist, was one such speaker. During Beutel’s presentation, entitled “An Editorial Cartoonist Confronts Holocaust Issues”, he displayed over 100 cartoons and slides, 18 of which referenced one Malcolm Ross.

At the time of the workshop, Ross was employed in a non-teaching position by a New Brunswick school board. Between 1976 and 1991, he had held teaching responsibilities, but these were removed following a human rights inquiry that concluded he was an anti-Semitic racist (which decision Ross then challenged (unsuccessfully) through to the Supreme Court of Canada, and from there to the UN Human Rights Committee).

The inquiry’s finding that Ross was an anti-Semitic racist was founded upon views Ross had promulgated in books, a pamphlet, letters to newspapers and a television interview. Centrally, Ross claimed there was an international Jewish conspiracy to exaggerate the Holocaust.

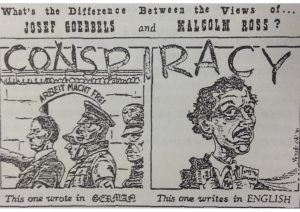

At the workshop, Beutel premiered his most controversial cartoon – the “Goebbels cartoon”.

Ross sat through Beutel’s presentation, which he tape-recorded and later transcribed.

Over the next two years, Ross issued proceedings for defamation against Beutel and the NBTA.

Ross’s complaint against Beutel centred on nine specific cartoons—including, of course, the Goebbels cartoon—and two excerpts gleaned from Beutel’s related commentary to the audience. Unusually for defamation proceedings, Ross did not allege that the material bore any specific meanings. Rather, he simply argued the cartoons were “defamatory”, “insulting”, “degrading”, “humiliating”, and that they “directly, personally and deliberately insulted [him] and his religious faith, and held him up to contempt and ridicule and abuse in front of his fellow teachers at a meeting of the NBTA”.

Beutel raised two defences: qualified privilege and fair comment. He pleaded 45 particulars of fact which he said supported his comments regarding Ross. This mainly included excerpts of Ross’s published views and beliefs.

Ross additionally sued the NBTA, which he argued was vicariously liable for hosting the workshop.

Judgment

In February 1998—that is, almost 5 years following the workshop—a 3-week trial was held in Moncton, New Brunswick, before Justice Creaghan.

In his judgment dated 17 April 1998, the Judge opened accordingly:

Malcolm Ross was raised the son of a Presbyterian minister in rural Northumberland County, New Brunswick, while Josh Beutel was raised in the tradition of the Montreal Jewish community. These divergent backgrounds may not go to the legal issues before me but they colour the fabric of the deep-seated emotion that permeated this case.

The Judge made clear it was not the function of the Court to determine whether Ross’s views were “good or bad or whether they should be supported or opposed”. The Court’s role was simply to determine whether Ross was entitled at law to damages for defamation.

On the evidence presented to the Court, the Judge found Beutel’s presentation “included cartoons and dialogue that, by any reasonable interpretation, a right-thinking person would find depicted Malcolm Ross as an anti-Semite, a racist and a Nazi”. The Judge, building on his finding that Ross was conveyed as a Nazi, held that, correspondingly, Beutel’s presentation was therefore understood to mean Ross was someone who would “advocate a policy of extermination” of the Jewish people.

Unsurprisingly, such meanings were found to be prima facie defamatory.

As a result, the onus fell on Beutel to make out a defence. For some unknown reason, the defence of qualified privilege was not considered by the Court. That left Beutel’s defence of fair comment (known in New Zealand since 1 February 1993 as “honest opinion”). Justice Creaghan resolved that Beutel had to prove that:

-

the three meanings the Court found Beutel’s presentation conveyed represented an honest expression of Beutel’s views;

-

his presentation was “of public interest”; and

-

the three meanings were “comment on true facts” – i.e. that the meanings were conveyed as Beutel’s opinions upon a proven factual basis, rather than conveyed as bald statements of fact (for which the defence would be unavailable).

The Judge had no problem determining that Beutel’s presentation represented his honestly held views concerning Ross – i.e. that Ross was an anti-Semite, a racist and a Nazi. Nor, given Ross’s public notoriety, did the Judge consider it could be disputed Beutel’s presentation concerned a matter of public interest.

The most pressing issue was whether Beutel’s presentation went beyond commentary on facts established at trial, and conveyed false statements of fact.

In respect of the first meaning, the Judge was satisfied the defendants had shown Ross to be an “anti-Semite”:

in the sense that his publications and his testimony at trial established that he takes vehement opposition to Judaism as an enemy of his religious beliefs. In the specific context of the Holocaust, I am satisfied that Mr. Ross views that historic occurrence as exaggerated by Jews as a tool to implant guilt in the minds of Christians as a means to effect compromise of what he sees as traditional Christian beliefs.

The Judge was also satisfied Beutel had shown Ross to be a “racist” in the sense that Ross’s publications and testimony at trial established that he saw himself as a member of a northern European Caucasian race whose racial identity was important to preserve; that he stood opposed to the intermingling of the races; that he saw God as giving different qualities to different peoples; and that he supported keeping “whites white and blacks black”. The Court opined that Ross’s stated analogy, that some horses are for show and some are for ploughing, “smacks of racist elitism”.

However, when the Judge came to assess Beutel’s defence to the meaning that Ross was a Nazi, Beutel ran into trouble. Ross had objected strongly to being “painted with the same brush as Nazis”. Ross had pointed to the Nazi philosophy as being “anti-religious”, which he said was the antithesis to his position.

Beutel, for his part—and backed by the NBTA—argued that Ross’s views on Judaism and race could be embraced by Nazi philosophy; pointed out that Nazi leaders and supporters had made statements that were compatible with Ross’s views regarding Jews and race; and drew the Court’s attention to meetings at which both Ross and Nazi sympathisers were present.

But Justice Creaghan could not be moved. He held that Ross’s views were founded on personal religious beliefs and not in any substantive way on Nazism; and, therefore, Beutel’s comments went “too far” to be defended as fair comment:

To suggest that Mr. Ross would advocate a policy of extermination as a solution to what he perceives as a spiritual battle against Judaism has not been established as fact.

Accordingly, the Court held that Ross was entitled to damages, which the Judge assessed at $7,500 (in 2016, approximately CAD$10,500 – or NZD$11,500).

Finally, the Judge held that the NBTA was not vicariously liable for Beutel’s comments: Beutel could not be regarded as an NBTA representative; nor could NBTA’s failure to apologise to Ross be regarded as ratification of Beutel’s comments. However, the Judge ordered the NBTA, rather than Beutel, to pay Ross’s costs. This was on the basis that NBTA had, according to the Judge, paved the way for such a dispute through its “ill advised” timing of the workshop:

The New Brunswick Teachers’ Association knew, or should have known, that given the high social and legal profile of the subject matter and the parties interested, the potential for problems, including possible defamatory remarks, was present.

Appeal

Both Beutel and Ross appealed the decision to the New Brunswick Court of Appeal. Almost two years later, the appeal was heard on 20 and 21 January 2000 before a 3-judge panel (Daigle CJ and Turnbull and Larlee JJA).

Beutel argued Creaghan J had erred in two respects. First, he argued the Judge had wrongly subjected the cartoon to a literal interpretation to conclude it was defamatory. Beutel argued that, in doing so, Creaghan J had ignored the very nature and essence of editorial cartoons, which Beutel said are based on allegory, caricature, analogy and ludicrous juxtaposition.

Secondly, Beutel argued that, even if his presentation was defamatory of Ross, the defence of fair comment should have been upheld.

Ross’s cross-appeal was brought on the basis that the Judge had erred by lumping together Ross’s multiple complaints of defamation: that he had not assessed each of the 5 cartoons complained of individually and made separate awards of damages for each.

For the hearing of the appeal, several ‘interveners’ made submissions in support of Beutel’s position. (Interveners are non-parties to a dispute who are given standing by the Court to make submissions in respect of the legal issues being canvassed, usually on the basis that the issues touch on their social or political interests.) The interveners in this case were:

-

Canadian Newspaper Association;

-

Association of Canadian Editorial Cartoonists;

-

Canadian Jewish Congress;

-

League of Human Rights of B’Nai Brith Canada; and

-

Canadian Civil Liberties Association.

No doubt extra seating had to be arranged.

Judgment

Sixteen months after the hearing, on 31 May 2001, the Court of Appeal released its decision.

In relation to Beutel’s appeal, the Court found that the trial judge had erred by finding that the Goebbels cartoon—on which the Court centred its decision—would have been understood by the teachers, as ordinary and reasonable viewers and listeners, to mean that Ross was “a Nazi who advocated the extermination of the Jewish people”. They recorded that, for the purpose of defamation, reasonable people would understand that cartoons were exaggerated statements, often invidious and virulent, but not to be taken literally:

To accept the allegations of fact that Ross ascribed to each cartoon is to ignore the very nature and essence of cartoons and the message they convey.

The Court of Appeal held that the inference properly drawn from the cartoon was that the plaintiff and Goebbels held substantially the same views on the issue of an alleged international Jewish conspiracy. This, ultimately, was still held to be a defamatory statement, so the Court was nevertheless required to consider Beutel’s challenge of the trial judge’s ruling on fair comment.

The Court of Appeal determined the trial judge was wrong to reject the defence. It held the inference to be drawn from the Goebbels cartoon—of similarity of views between Goebbels and Ross—constituted Beutel’s comment. As to the degree of facts Beutel was required to establish to support the comment, the Court held that, to be protected, the comment need not be proven to be “true”, but simply fair or relevant in the sense that it related to the proven underlying facts on which the commentator relied. The Court was satisfied that Beutel’s defence met this element and, thus, it held Ross’s claim should have been dismissed.

Dealing with Ross’s cross-appeal, the Court agreed with Ross—as did, ironically, Beutel’s counsel—that the trial judge should have made separate findings regarding the five cartoons complained of: that is, the trial judge should have ruled on each alleged defamation as if it were a separate cause of action. However, the Court held that no substantial wrong had been occasioned to Ross because the evidence presented at trial had overwhelmingly supported the finding that Ross was a racist and an anti-Semite. Therefore, the underlying facts indicated in each of Beutel’s cartoons was substantially true so as to support Beutel’s honestly held beliefs.

Comment

-

This case is proof that, contrary to many journalists’ beliefs, there is no exception in the law of defamation for cartoons.

-

Given that it took almost 8 years from the time of the workshop for the case to be determined by the Court of Appeal, one lesson for intending defamation litigants is to pack a lunch and get comfy – you may there for a while!